The Quantization Cliff: When Does Compression Break Code Intelligence?

Testing GLM 4.5 Air from 4-bit to 1-bit: A Tetris coding experiment reveals where model compression crosses from viable to broken

Modern language models have reached extraordinary capabilities, but their size remains a practical barrier. A 671B parameter model like DeepSeek-V3.1 requires ~1.3TB in full precision—impossible for most developers to run locally. Quantization promises a solution: compress models by representing weights with fewer bits, trading marginal accuracy for dramatic size reduction.

But where does compression stop being a “tradeoff” and become a fundamental degradation of capability? To answer this, I ran a simple but revealing experiment: asking GLM 4.5 Air (106B parameters, 12B active in MoE architecture) to implement Tetris at progressively extreme quantization levels.

What Is Quantization?

Language models store their learned knowledge in billions of floating-point weights—typically 16-bit (BF16) or 32-bit (FP32) precision. Quantization compresses these representations by using fewer bits per weight. An 8-bit quantized model uses 8x less memory than FP32, a 4-bit model uses 16x less, and so on.

The naive approach—uniformly rounding all weights to lower precision—destroys model quality. Modern quantization is selective: critical layers (attention projections, certain feed-forward components) retain higher precision, while less sensitive parameters get compressed more aggressively. The weights are grouped into blocks, each with its own scale factor, enabling piecewise-linear approximation of the original distribution.

K-quants (Q2_K, Q3_K, Q4_K, etc.) use a two-level quantization scheme: small blocks with individual scales grouped into super-blocks with additional scaling. The suffixes (S/M/L/XL) indicate how aggressively different tensor types are quantized—XL variants keep important matrices at higher precision.

Dynamic quantization (like Unsloth’s approach) goes further: different layers within the same model use different bit-widths based on sensitivity analysis. A MoE model might quantize unimportant expert layers to 1-bit while keeping attention mechanisms at 6-8 bits.

The Experiment: Tetris as a Complexity Benchmark

I chose a specific task: “Create a complete Tetris game in a single HTML file.” This requires:

Algorithmic correctness: Collision detection, rotation matrices, line clearing

State management: Game loop, scoring, level progression

API knowledge: Canvas rendering, event handling, DOM manipulation

Architectural coherence: Organizing code into maintainable structures

The task is complex enough to stress the model’s capabilities but simple enough that correctness is binary—the game either works or it doesn’t.

We tested three quantization levels using Unsloth’s dynamic quantization:

Q4_K_XL (~4-bit average): Critical layers at 5-6 bits, bulk of model at 4 bits

Q2_K_XL (~2-bit average): Critical layers at 3-4 bits, bulk at 2 bits

TQ1_0 (~1.6-bit average): Critical layers at 4-6 bits, unimportant MoE experts at 1 bit

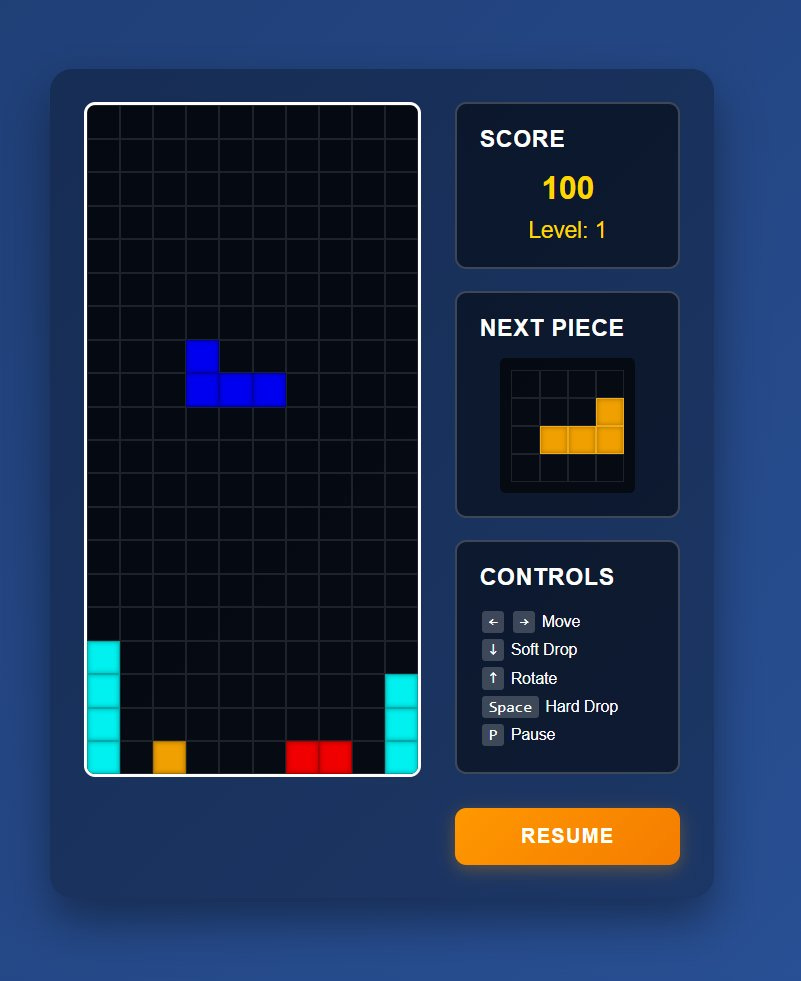

Q4_K_XL: Near-Lossless Code Generation

The 4-bit quantized model produced professional-grade code. The implementation demonstrates:

Architectural sophistication: Clean object-oriented design with separate Tetromino and Game classes, proper encapsulation, no global state pollution.

Algorithmic correctness: The collision detection iterates correctly over the shape matrix with proper boundary checking on all three axes. The rotation logic implements the standard transpose-and-reverse transformation. Line clearing uses Array.splice with correct index compensation after removal.

Gameplay mechanics: The scoring system implements the classic Nintendo schema: [40, 100, 300, 1200][linesCleared - 1] * level. Hard drop vs. soft drop differentiation is correct (2pts vs. 1pt). The fall speed reduces logarithmically: Math.max(100, 1000 - (level - 1) * 100).

Modern best practices: Uses requestAnimationFrame for the game loop, implements proper event delegation, includes glassmorphism UI with backdrop filters, responsive design with media queries.

The game is fully functional and indistinguishable from what a human developer would produce. If you didn’t know it was generated by a quantized model, you wouldn’t guess it.

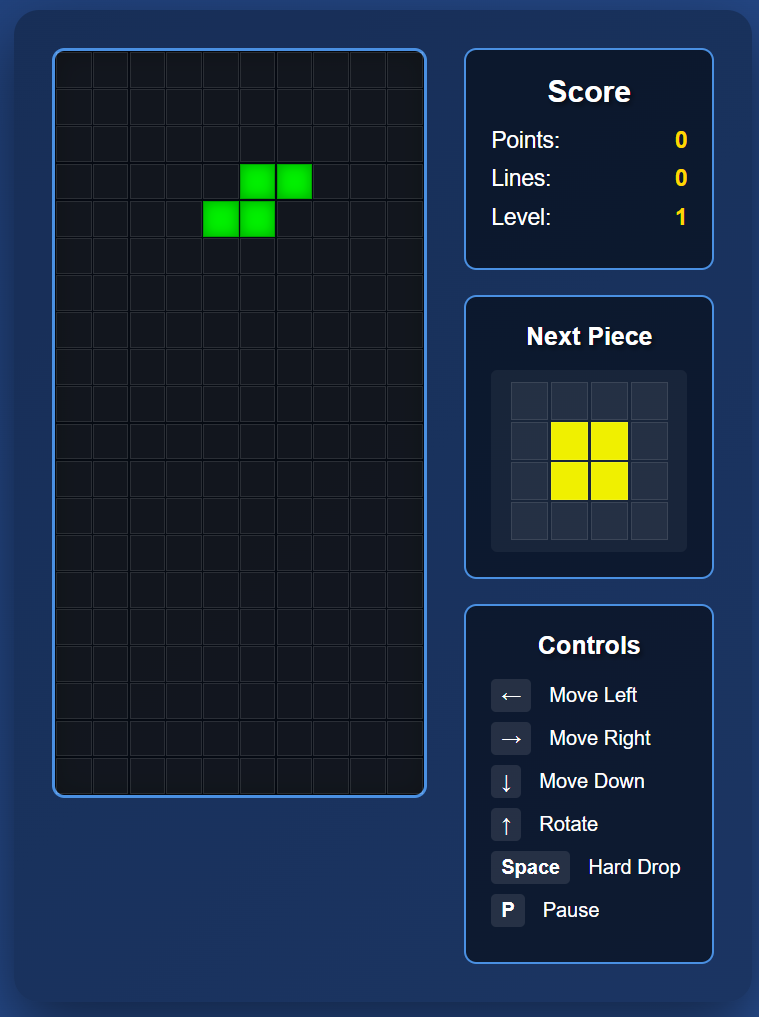

Q2_K_XL: Functional but Degraded

At 2-bit quantization, cracks begin to appear. The game still works, but architectural quality degrades noticeably:

Rendering pipeline shift: Instead of Canvas with direct pixel manipulation, the code switches to DOM-grid manipulation with CSS classes. This isn’t wrong, but it’s conceptually simpler—suggesting the model fell back to more robust patterns when precision decreased.

Loss of abstraction: The clean OOP structure vanishes. Instead of encapsulated Tetromino classes, the code uses procedural functions and global state. The shape definitions remain correct, but they’re now plain objects created by factory functions rather than proper class instances.

Algorithmic integrity preserved: Remarkably, the core algorithms remain correct. The collision detection logic is identical to Q4_K_XL. The rotation matrix transformation works. Line clearing with splice + unshift functions properly.

Suboptimal API choices: The code reverts to setInterval instead of requestAnimationFrame. This works but lacks vsync synchronization and automatic pausing on tab switch—the “knowledge” of modern browser best practices has degraded.

Simplified scoring: Instead of the exponential line-clear rewards, scoring becomes linear: linesCleared * 100 * level. The nuance is lost, but the mechanism functions.

The game is fully playable. A casual user wouldn’t notice the difference. But the code shows clear “code smell”—it works, but it’s no longer state-of-the-art.

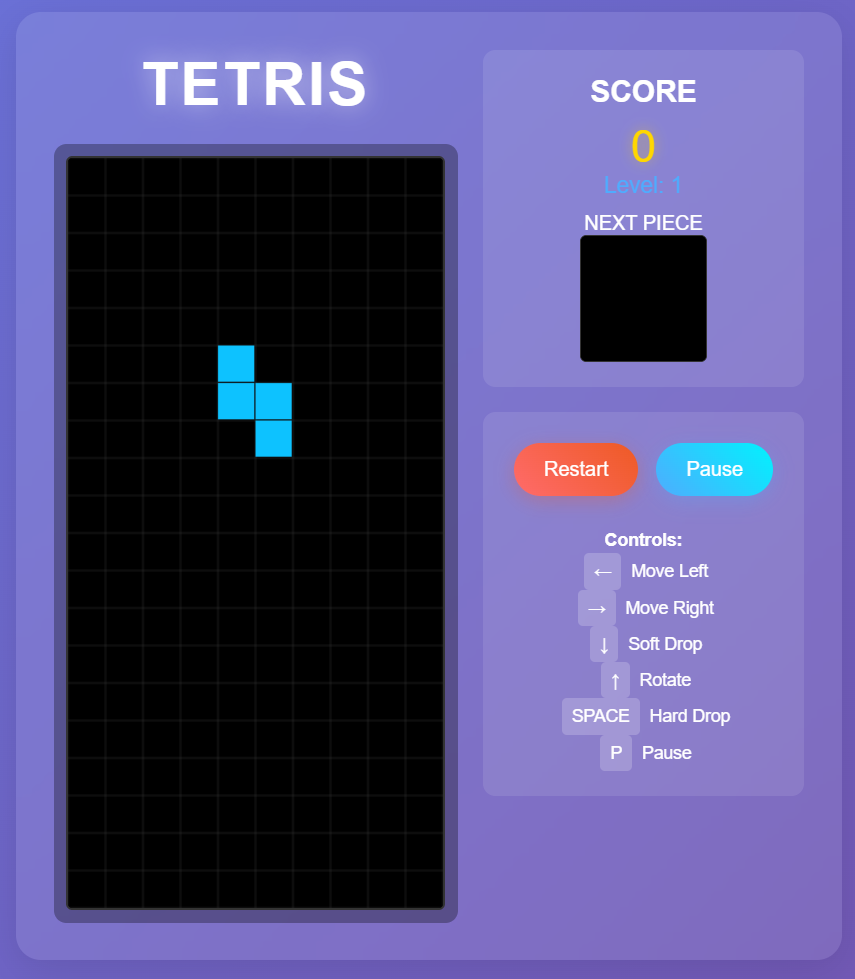

TQ1_0: The Coherence Threshold

At ~1.6 bits, functional integrity begins to collapse. The game runs, but it’s fundamentally broken:

Corrupted shape definitions:

const pieces = [

[[1,0,0],[1,0,0],[1,1,0]], // L - correct

[[1,0,0],[1,1,0],[0,1,0]], // J - correct

[[1,1,1],[0,1,0]], // T - correct

[[1,1,1],[1,1,1]], // Square - WRONG: 6 blocks instead of 4

[[1,0,0,0],[1,0,0,0],[1,1,0]], // Long - WRONG: not a valid tetromino

[[1,1,0],[0,1,1]], // Z - correct

[[0,1,1],[1,1,0]] // S - correct

];

The model “knows” it needs to define Tetris pieces, but the exact matrix structures are corrupted. The I-piece (the iconic straight line) is completely missing. The square piece has become a 3×2 rectangle.

Broken preview rendering: The next-piece canvas remains empty. The rendering logic exists and is mathematically correct, but it references wrong coordinate systems—pieces render off-screen.

UI layout degradation: The controls section loses its structured formatting, becoming chaotic inline text. The model has regressed from semantic HTML structures to primitive <br> tags.

Class structure inconsistency: The Piece class still exists (unlike Q2_K_XL’s full regression to procedural code), but its methods are partially broken. The rotation validation creates a temporary object without copying the current position—validation checks the wrong coordinates.

The game is playable for about 30 seconds before users realize something is fundamentally wrong. This is the threshold where quantization shifts from “engineering tradeoff” to “unsuitable for production.”

The Benchmark Correlation

These subjective observations align precisely with Aider Polyglot benchmarks measuring coding ability:

Quantization Aider Score Size (DeepSeek-V3.1) Tetris Quality 8-bit 71.6% 671 GB Baseline 5-bit 70.7% ~420 GB Near-identical 4-bit 69.7% ~387 GB Professional 3-bit 68.4% ~300 GB Still solid 2-bit 65.8% ~255 GB Functional, degraded 1-bit 55.7% ~170 GB Fundamentally broken

The degradation is non-linear. From 8-bit to 2-bit, you lose only 5.8 percentage points while reducing model size by 75%. The “plateau of stability” spans 5-bit to 2-bit—a massive range where quantization remains viable.

But below 2-bit, performance collapses. The drop from 2-bit (65.8%) to 1-bit (55.7%) represents a 10-point loss—nearly double the entire degradation from 8-bit to 2-bit.

Why Coding Tasks Are Quantization-Resistant

The relative robustness of coding performance under quantization likely stems from the discrete, syntactic nature of programming languages. Code operates in binary states: it compiles or it doesn’t, the algorithm works or it fails.

Token probability distributions for syntax-critical elements (brackets, operators, keywords) are highly concentrated. There’s exactly one correct way to transpose a matrix or check boundary conditions. The probability mass clusters around canonical patterns.

In contrast, natural language generation involves continuous semantic spaces where subtle nuances matter. Creative writing, nuanced argumentation, or contextual understanding degrade more gracefully but also more pervasively under quantization.

This suggests quantized models may be particularly viable for code generation, infrastructure automation, and other structured tasks—precisely the domains where local deployment matters most due to privacy and latency requirements.

Practical Implications

For developers deploying locally: Q4_K_XL represents the sweet spot. You get 75-80% size reduction with <3% performance degradation. A 100B parameter model becomes runnable on high-end consumer hardware (64-128GB RAM + GPU). The code quality remains production-grade.

The 2-bit boundary: Q2_K_XL is the practical lower limit for professional applications. Code will function but show architectural weaknesses. Suitable for prototyping, learning, or non-critical automation, but not for production systems where code quality matters.

Below 2-bit is research territory: TQ1_0 and similar extreme quantizations are fascinating for understanding model compression limits but unsuitable for real work. The 75% size reduction (671GB → 170GB) seems attractive, but the functional compromises are too severe.

Dynamic quantization is essential: Naive uniform quantization at these bit levels would produce gibberish. The only reason Q2_K_XL and even TQ1_0 produce anything functional is selective preservation of critical layers at higher precision.

The Infrastructure Gap

These experiments highlight a critical gap in the AI ecosystem. Benchmark numbers (71.6% vs. 69.7%) sound abstract. Telling developers “you’ll lose 2 percentage points” doesn’t convey the practical reality.

What developers need to know: Will my 4-bit model write correct collision detection? Will rotation matrices work? Will the game loop handle timing properly?

The answer for Q4_K_XL is definitively yes. For Q2_K_XL, mostly yes with caveats. For TQ1_0, no—expect fundamental failures.

Quantization isn’t a spectrum of gradual degradation. It’s a cliff. You can compress aggressively within a safe zone, then capability collapses rapidly once you cross the threshold. For coding tasks with current techniques, that threshold sits somewhere between 2-bit and 1.6-bit.

Understanding where your use case falls on this cliff is critical for making informed deployment decisions. The 80% size reduction from Q4_K_XL isn’t just a number—it’s the difference between needing a server rack and running on a MacBook Pro.

All code samples and benchmark data are available in the [repository]. The GLM 4.5 Air model was tested using Unsloth’s dynamic quantization GGUFs, chosen specifically for their sophisticated layer-selective approach and extensive calibration.