Can Parameters Compensate for Aggressive Quantization?

When a 355B model with 1-bit dynamic quantization loses to a 106B model at 4-bit — and what it means for local LLM deployment. A Real-World Test.

We recently ran an experiment that challenges a common assumption in the LLM space: that more parameters can offset the quality loss from aggressive quantization. Using two massive Chinese language models from Zhipu AI — GLM 4.6 (355B parameters) and GLM 4.5 Air (106B parameters) — we tested whether sheer model size could rescue performance when quantization is pushed to the extreme.

The comparison was deliberately unfair in one direction: GLM 4.6 represents a newer architecture than 4.5, has been further optimized for coding tasks, and contains more than 3× the parameters. If parameter count could compensate for quantization degradation, this should be the scenario where it works.

Hardware context: Both models ran on an AMD Strix Halo APU with 128GB unified LPDDR5X quad-channel RAM — a configuration that represents the cutting edge of consumer-grade local inference. The unified memory architecture eliminates PCIe bottlenecks and makes running models of this scale feasible on a single machine.

Quantization methods:

GLM 4.6: TQ1_0 dynamic quantization (78.2 GB on disk)

Performance: 8-10 tokens/second with ~32B active parameters (MoE)

GLM 4.5 Air: Q4_K_XL quantization (67.9 GB total)

Performance: 15-20 tokens/second with ~12B active parameters (MoE)

Understanding TQ1_0: Unsloth’s Dynamic Quantization

Before diving into results, it’s critical to understand what TQ1_0 actually does. This isn’t naive 1-bit quantization across the board — that would produce gibberish.

TQ1_0 (Ternary Quantization 1.0) is part of Unsloth’s “Dynamic Quantization” approach, which selectively applies different bit-widths across layers:

1-bit for unimportant layers (primarily in MoE expert layers that aren’t frequently activated)

2-4 bit for moderately important layers (most MoE layers)

6-8 bit for critical layers (attention mechanisms, key/query/value projections, final output layers)

This selective approach has shown remarkable results on benchmarks like Aider Polyglot, where Unsloth’s dynamic 3-bit DeepSeek V3.1 GGUF achieved 75.6% accuracy, surpassing many full-precision models. The method works especially well for MoE architectures like GLM 4.6, where only a fraction of parameters activate for any given token.

The total effective bit-width averages around 1.6-1.7 bits per weight — hence “TQ1_0” — but the distribution is highly non-uniform.

Q4_K_XL is also a mixed-precision scheme (the “K” suffix indicates K-quants, which apply different bit-widths by layer importance), but far more conservative:

Q6_K (6-bit) for critical attention layers (attention.wv, feed_forward.w2)

Q4_K (4-bit) for most other tensors

This averages around 4.5 bits per weight depending on model architecture.

Theoretical capacity calculation:

GLM 4.6 TQ1_0: 355B × ~1.7 bits = 603.5 Gb effective capacity

GLM 4.5 Air Q4_K_XL: 106B × ~4.7 bits = ~498 Gb effective capacity

The gap is narrower than it first appears — only ~22% more capacity in the larger model. But does that translate to better outputs?

Test 1: Code Generation

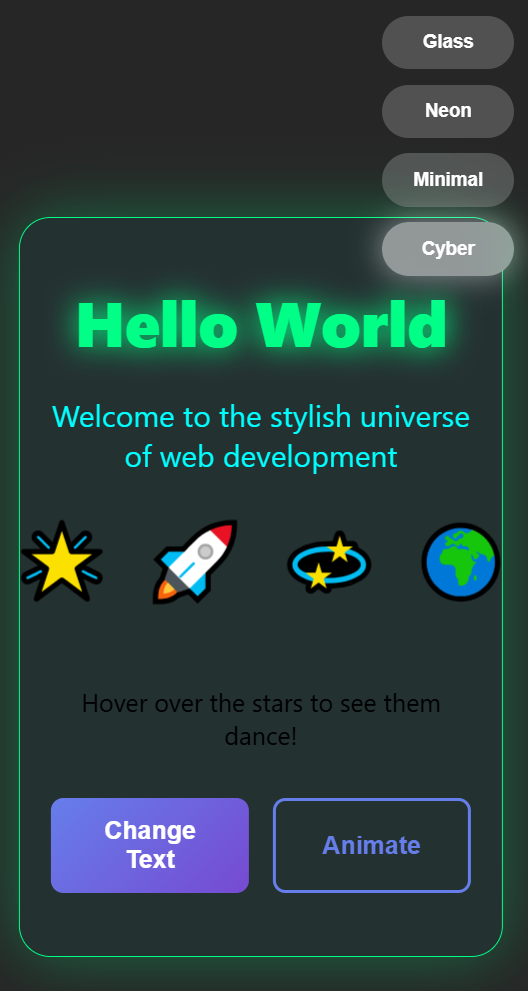

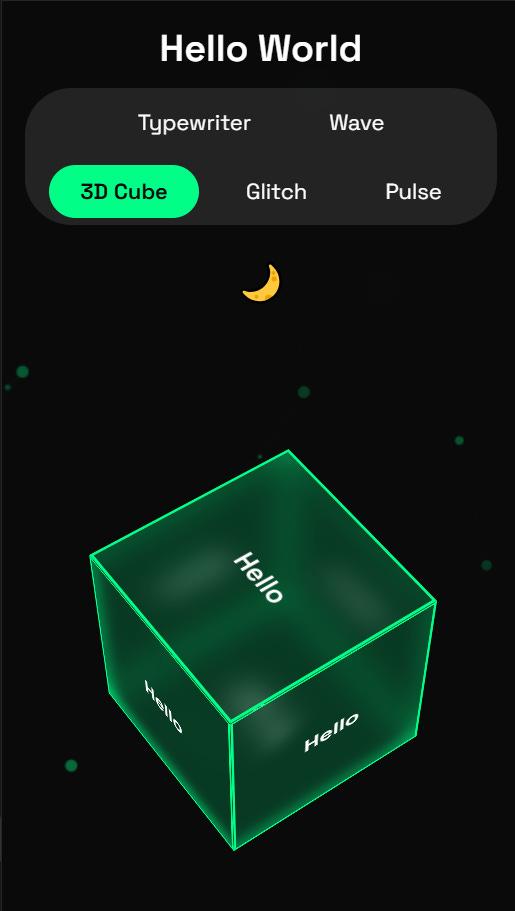

Task: Create a stylish “Hello World” webpage with multiple visual modes, animations, and interactive elements.

This is an ideal test for coding ability — it requires:

Syntactic precision (HTML/CSS/JavaScript)

Structural coherence (managing multiple visual themes)

Attention to detail (responsive design, animations)

Results

GLM 4.6 (355B @ TQ1_0): Produced structurally coherent but systematically broken code. The failures aren’t isolated — they reveal categorical precision loss:

JavaScript syntax errors:

// Line 376: Token collision

particleconst = particle.style.animationDelay = `${Math.random() * 5}s`;

// The model conflated ‘particle.style’ with ‘const particle’

// Lines 472-473: Missing CSS units

dot.style.left = e.pageX; // Should be: e.pageX + ‘px’

dot.style.top = e.pageY; // Should be: e.pageY + ‘px’

HTML/CSS structural errors:

JavaScript references

document.getElementById(’particles’)expecting a<canvas>HTML provides

<div id=”particles”>— type mismatch breaks renderingParticle animations use

position: absolutewithtranslateY(-100vh)(incompatible)Subtitle starts at

opacity: 0with animation but never gets activated

Logic errors:

Interactive text opacity controlled by both CSS animation and setTimeout — race condition

Mouse trail creates elements but array management broken (elements leak)

Float animation assumes fixed positioning but particles are absolutely positioned

The model understood the task (particle system, style switcher, animations) but failed at dozens of implementation details. It’s not “code with a bug” — it’s code with systematic precision failure.

GLM 4.5 Air (106B @ Q4_K_XL): Generated completely functional code with:

Proper syntax throughout — no token collisions, no missing units

Working 3D CSS cube with precise transform calculations

Particle system with correct canvas rendering

Responsive design that adapts correctly to all screen sizes

Clean event handler logic without race conditions

The pattern of degradation:

The 355B model’s errors aren’t random. They cluster precisely where local context disambiguation is required:

particleconst— conflating two tokens with overlapping context windowsMissing

‘px’units — forgetting syntax details while attending to semantic contentHTML/canvas mismatch — losing track of type compatibility across ~100 lines of code

Animation positioning errors — failing to maintain consistency between CSS properties

At 1-bit quantization, attention heads can only make binary decisions. When two tokens are contextually similar (particle.style vs. const particle), the model can’t resolve which is correct — it blends them.

The difference wasn’t marginal — it was categorical. One model produced deployable code; the other produced non-functional output that looked structurally plausible but failed on execution.

Test 2: Low-Resource Language Translation

Task: Translate a nuanced English paragraph to Kiswahili (Swahili).

The test paragraph contained:

Concrete objects (fisherman, nets, tea)

Temporal markers (morning, tomorrow)

Complex syntax (relative clauses with “where”)

Narrative perspective (”he thought”)

This tests whether the larger model’s extra capacity preserves knowledge of less-represented languages.

Results

GLM 4.6 (355B @ TQ1_0):

Mzamaki mzee alikuwa akishambilia mavuao wake pambeleni bahari,

akaliangalia ulewele ambako mawingu ya mbubu yalikuwa yakijumuika.

Bint wake akampatia chai bado joto kutoka kwa moto wa asubuhi.

Ndani akafikiria, “Kesho, samani itakuwa tulivu tenata.”

Critical errors:

“Mzamaki” — not a real Kiswahili word (hallucinated from phonological patterns)

“Mavuao” — non-standard for “nets” (correct: “nyavu”)

“Samani” — means “furniture,” not “sea” (correct: “bahari”)

“Tenata” — doesn’t exist (likely contamination from “tena” = again)

The model then provided an elaborate glossary inventing etymologies for these non-existent words: “from mzamaki - fisherman, and mzee - elder/old” — pure confabulation.

GLM 4.5 Air (106B @ Q4_K_XL):

Mzee mwamba alikuwa akifunga chanda zake kwenye ufuko,

akangalia mbali kwenye horizon ambapo mawingu ya mvua yalikuwa yakiunganika.

Binti yake alipelekea chai yake, iliyobaki moto kutoka jikoni ya asubuhi.

Kesho, alifikiria, bahari itakuwa salama tena.

Mostly correct:

“Bahari” (sea) — correct

“Chai” (tea) — correct

“Kesho” (tomorrow) — correct

“Asubuhi” (morning) — correct

Syntax and grammar largely coherent

The one questionable term was “mwamba” (which primarily means “rock/stone”), but Google Translate suggests this can be used idiomatically for “old man” in some contexts. Regardless, the model used real words rather than hallucinating an entire lexicon.

What’s Actually Happening?

The failure pattern is consistent and illuminating.

Code Generation: Loss of Local Consistency

The particleconst bug reveals that at 1-bit quantization, the model loses the ability to maintain local syntactic coherence. The semantic intention is correct (assign animation delay to particle), but the execution fragments.

This happens because 1-bit quantization forces attention weights into binary decisions: “relevant” or “not relevant.” The model can’t distinguish between “syntactically correct” and “semantically similar but syntactically wrong.”

At 4-bit, the attention mechanism retains enough resolution to disambiguate between particle.style, const particle, and particle.style.animationDelay because each has a distinct activation pattern in the higher-precision weights.

Translation: Epistemological Collapse

The Kiswahili results are more subtle but more damaging. The 355B model doesn’t just make errors — it loses the ability to know what it knows.

When a model with sufficient precision encounters a low-confidence situation (like translating to an underrepresented language), it should either:

Use a suboptimal but real word

Indicate uncertainty

Fall back to a known pattern

At 1-bit quantization, the confidence calibration breaks. The model generates tokens that match the phonological and morphological patterns of Kiswahili (Bantu prefix structure, agglutination, vowel harmony) but are lexically invented.

This is precisely analogous to certain forms of aphasia: the patient produces fluent, grammatically structured speech that consists of non-words (”neologistic jargon aphasia”). The structural competence remains; the lexical grounding is lost.

The Critical Phase Transition

There’s a non-linear relationship between quantization and capability degradation.

At 4-bit quantization:

16 discrete values per weight

Attention heads can distinguish between multiple contextually similar tokens

Uncertainty estimates remain calibrated

The model “knows what it doesn’t know”

At 1-2 bit quantization (even dynamically applied):

2-4 discrete values per weight

Attention collapses to binary relevance judgments

Confidence calibration breaks

The model confabulates when uncertain

The gap between 4-bit and 1-bit isn’t 4× — it’s exponential in information-theoretic terms: 2^4 = 16 states vs. 2^1 = 2 states.

Crucially: The 355B model has more total capacity (603.5 Gb vs. 420 Gb), but that capacity is spread across weights quantized so aggressively that they can’t represent the functions they’re trying to compute.

It’s like having a very large image sensor (megapixels) but terrible optics. The sensor can’t rescue what the lens has already blurred.

Why Code Suffers More Than Conversation

Code is a formal system with zero fault tolerance. A single misplaced token causes runtime failure.

Natural language has redundancy. Even with errors, semantic content often gets through. This is why LLMs can seem “good enough” at 2-bit quantization in casual conversation — the human reader fills in gaps.

But code exposes the underlying degradation immediately. There’s no “close enough” in syntax trees.

This explains why:

The 355B model could still generate plausible-looking code structure

But failed at precise token sequences (

particleconst)While in Kiswahili translation, it produced plausible-sounding output that was lexically nonsense

Both failures stem from the same root cause: loss of fine-grained discriminative capacity in attention mechanisms.

The Latency-Quality Double Bind

The 355B model isn’t just lower quality — it’s also slower:

8 tokens/second vs. 15-20 tokens/second

Higher memory consumption

There’s no compensation mechanism. You get worse outputs and wait longer for them.

This is the opposite of what we’d hope for in a size-quality tradeoff.

So When Would 355B @ TQ1_0 Win?

Theoretically, there are narrow cases where more parameters + extreme quantization could outperform fewer parameters + conservative quantization:

Pure retrieval over massive context (no generation)

If you’re just searching for semantic matches across 100k+ token contexts

Syntactic precision doesn’t matter

The extra capacity could help

Multilingual classification (not translation)

Detecting “is this text in language X or Y?”

Phonological patterns preserved even at low bit-width could suffice

No need to generate grammatically correct output

Fuzzy semantic similarity in obscure domains

“Find papers related to Sufi poetry from the 14th century”

More parameters = more long-tail knowledge embedded

Low precision might not destroy high-level semantic clustering

But these are edge cases, and even then, you’d likely use a specialized embedding model rather than a generative LLM.

For any task requiring generation (code, writing, translation, reasoning), the 106B @ Q4 dominates.

What This Means for Local Deployment

The practical implication is clear: the sweet spot for local inference is ~70-200B parameters at Q4-Q6 quantization, not 300B+ at Q1-Q2.

This configuration:

Fits on high-end consumer hardware (128GB unified memory)

Maintains epistemic calibration (the model knows when it’s uncertain)

Preserves syntactic precision for structured tasks

Delivers acceptable latency (15-30 tokens/second)

Going bigger with more aggressive quantization doesn’t improve the tradeoff — it makes it worse on both axes.

The Deeper Lesson: Information Density vs. Information Volume

This experiment illustrates a fundamental principle: precision per bit matters more than total bits when the precision falls below a critical threshold.

A 355B model at 1-bit average isn’t “a very compressed large model” — it’s a broken model with extra parameters.

Analogy: A 100-megapixel camera with a terrible lens produces worse images than a 24-megapixel camera with excellent optics. Resolution doesn’t rescue what’s already degraded.

In quantization, the “lens” is the bit-width per weight. Below ~3-4 bits, the representational capacity collapses faster than additional parameters can compensate.

Conclusion

Parameter count cannot compensate for aggressive quantization — at least not for tasks requiring generative precision.

The GLM 4.6 (355B) at TQ1_0 dynamic quantization lost decisively to GLM 4.5 Air (106B) at Q4_K_XL on:

Code generation (syntax errors, layout bugs)

Low-resource language translation (hallucinated lexicon)

Latency (8 vs. 15-20 tokens/s)

The failure wasn’t marginal — it was categorical. One model produced deployable outputs; the other produced plausible-looking failures.

For local LLM deployment, the winning formula is:

70-200B parameters

Q4-Q6 quantization (not lower)

Conservative quantization over parameter maximization

The future of local AI isn’t “compress the biggest model as hard as possible” — it’s “find the right model size that quantizes gracefully.”

And that size, empirically, is around 100B ± 50B at 4-bit precision.

Tested on AMD Strix Halo APU with 128GB LPDDR5X RAM. Models: GLM 4.6 (355B, TQ1_0, 78.2GB), GLM 4.5 Air (106B, Q4_K_XL, 67.9GB). All tests conducted December 2025.

Wow, the part about TQ1_0 dynamic quantization really stood out to me, making me think how crucial good quantization is for practical edge AI deeployment, even with huge models.