The Coding Model Myth: Why Specialization Makes AI Worse at Programming

Qwen3-Next vs Qwen3-Coder-Next, a Tetris game and the uncomfortable truth about what fine-tuning actually optimizes for

Here’s a simple experiment. Take two AI models from the same family - one general-purpose, one specialized for coding - and ask both to build a Tetris game in a single HTML file. You’d expect the coding model to win easily. It doesn’t. In fact, it produces something that doesn’t work at all, while the generalist delivers a playable game with some rough edges.

This isn’t an anomaly. It’s a symptom of something the AI industry doesn’t want to talk about: coding models can be systematically worse at programming than their general-purpose siblings, and the reason lies in what fine-tuning actually does to a neural network’s understanding of the world.

The Experiment

We gave the same prompt to Qwen3-Next (general-purpose) and Qwen3-Coder-Next (code-specialized). Both are from Alibaba’s latest Qwen3 family. The Coder variant was explicitly trained through supervised fine-tuning on high-quality agent trajectories, domain-specialized expert training, and reinforcement learning from execution environments. On paper, it should dominate any coding task.

The results tell a different story.

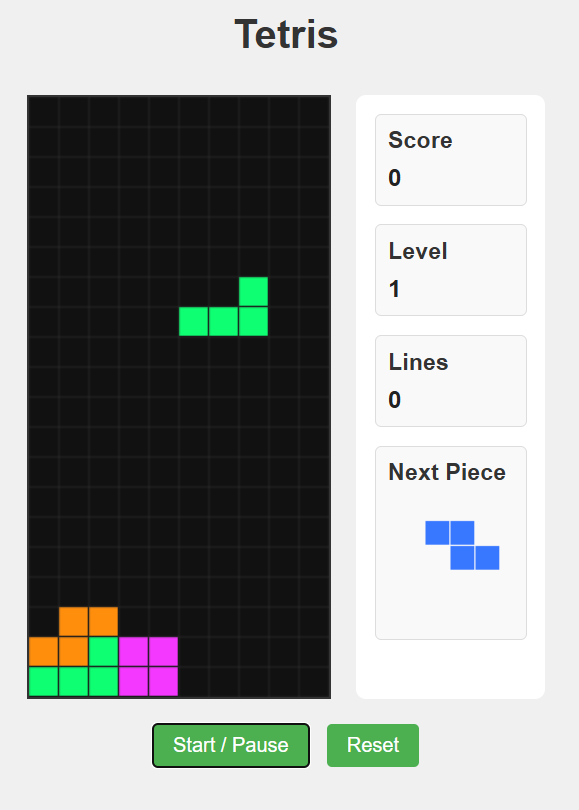

Qwen3-Next (the generalist) produced a Tetris game with some cosmetic bugs - a few missing values in arrays, likely tokenization artifacts - but with fundamentally sound game logic. You can play it.

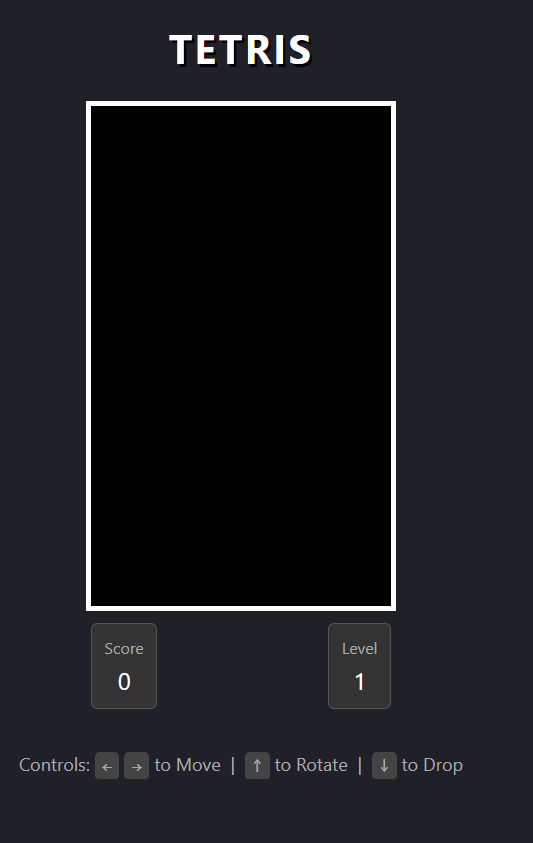

Qwen3-Coder-Next (the specialist) produced code that looks better on first glance. Darker theme, modern JavaScript patterns, elegant destructuring syntax, requestAnimationFrame instead of setInterval. The kind of code that would impress in a style review.

It doesn’t run.

And the gap isn’t a matter of one or two bugs. It’s a systematic collapse across nearly every layer of game logic.

The Full Autopsy

Let’s go through both outputs methodically. What follows isn’t cherry-picking - it’s the complete picture.

The Coding Model’s Failures

1. Collision detection is fundamentally broken.

This is the heart of any Tetris implementation - the function that determines whether a piece can move or has hit something. The coder wrote:

if (m[y][x] !== 0 &&

(arena[y + o.y] && arena[y + o.y][x + o.x]) !== 0) {

return true;

}Compact, idiomatic JavaScript. Also broken. When a piece spawns at the top of the board and y + o.y is negative, arena[y + o.y] returns undefined. The && operator passes undefined forward, undefined !== 0 evaluates to true - the game registers a collision where none exists. Pieces can trigger game-over the instant they appear. There’s also no explicit boundary check for walls or floor. The function relies entirely on JavaScript’s truthy/falsy behavior with undefined array accesses, which accidentally half-works for some edges and completely fails for others.

2. Line clearing has a syntax error.

outer: for (let y = arena.length - 1; y > ; --y) {That y > ; is not an edge case or a subtle logic bug. It’s a syntax error - a missing comparison value that kills the entire line-clearing mechanism. In a Tetris game without line clearing, you’re just stacking blocks until you lose. The core gameplay loop doesn’t exist.

3. The board dimensions are wrong.

createMatrix(12, 20) creates a 12-column arena. Tetris has 10 columns. The canvas math happens to be internally consistent (240px / scale 20 = 12 units), so the game renders without visual glitches, but the playing field is 20% wider than it should be. The model doesn’t know what Tetris looks like.

4. The scoring system is arbitrary.

player.score += rowCount * 10;

rowCount *= 2;This gives 10 points for the first cleared line, 20 for the second, 40 for the third, 80 for the fourth. That’s not the Nintendo scoring system (40/100/300/1200), not the Sega system, not any known Tetris scoring variant. It’s a generic exponential function - the kind of thing you’d write if you’d seen scoring code in training data but had no concept of what Tetris scoring is.

5. Level progression is broken beyond playability.

const level = Math.floor(player.score / 100) + 1;

dropInterval = Math.max(1, 1000 - (level - 1) * 100);After a single Tetris (four lines = 150 points), you’re at level 2. The drop interval formula means that by level 11 (achievable very quickly), pieces fall every 1 millisecond. The game becomes physically unplayable within minutes. The model has no conception of difficulty curves or how human reaction time constrains game design.

6. Uses deprecated APIs.

The coder uses event.keyCode for input handling - an API that has been deprecated for years in favor of event.key. For a model specifically trained on modern code patterns, this is an ironic regression.

7. Missing features: no pause, no next-piece preview, no hard drop, no mobile support.

The game has no pause functionality, no preview of the upcoming piece (a standard Tetris feature since the 1980s), no hard-drop (pressing space to instantly place a piece), and no touch controls for mobile. It’s a bare skeleton that’s missing most of what makes Tetris playable.

The Generalist’s Output

The generalist model’s code has its own problems - but they’re of a fundamentally different character.

The bugs are surface-level tokenization artifacts. Array values like [, , 0, ] instead of [0, 0, 0, 0], and rgba(, , 0, 0.3) instead of rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.3). These are systematic, predictable, and fixable with a simple find-and-replace. They’re artifacts of the output encoding, not failures of understanding.

The game logic is correct. The collision detection includes explicit boundary checks and a y + row >= 0 guard that shows the model understood pieces can exist partially above the visible board during spawn. The line-clearing function works. The board is 10 columns wide.

The scoring system is structurally correct. The values are garbled by the same tokenization issue ([, 4, 1, 3, 1200] instead of [0, 40, 100, 300, 1200]), but the architecture is right - it uses a lookup table indexed by number of lines cleared, multiplied by level. The model knows that Tetris has a specific, non-linear scoring system.

It implements features the coder doesn’t. Next-piece preview on a separate canvas. Pause functionality. Hard drop with spacebar. Touch controls for mobile with swipe detection. Lines-cleared counter. Level progression that scales reasonably (new level every 10 lines, matching the standard Tetris formula).

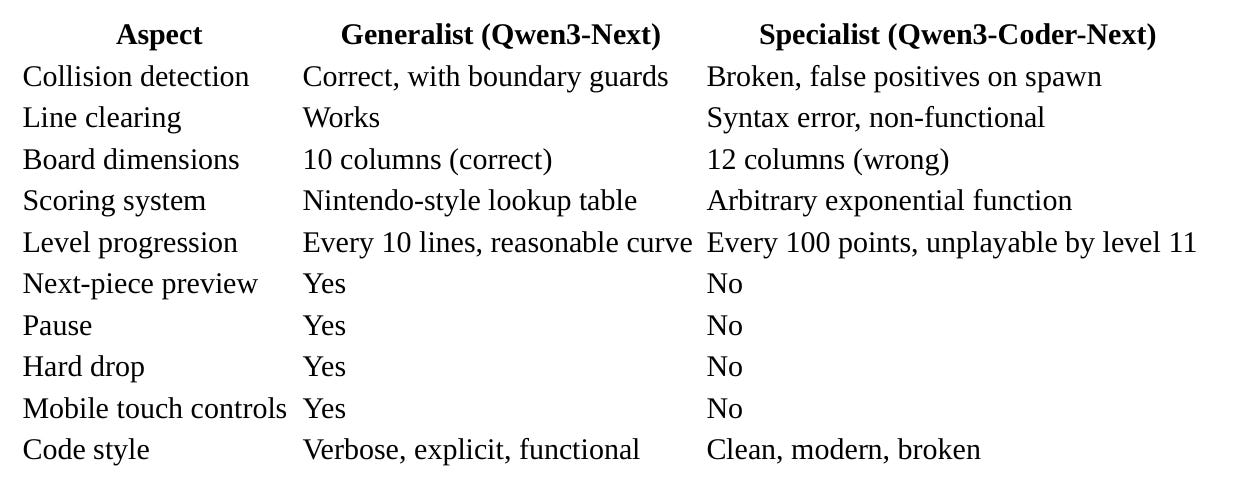

The Scorecard

Let’s make the discrepancy explicit:

The generalist wins on every dimension of functionality. The specialist wins on aesthetics - darker theme, cleaner variable naming, modern API usage (except for the deprecated keyCode). It’s a near-perfect inversion: the model trained to write better code writes prettier code that does less and works worse.

The Paradox of Specialization

How can a model fine-tuned specifically for coding produce worse code than a generalist? The answer requires recognizing that “writing code” is not one skill. It’s a composite of at least two fundamentally different cognitive operations:

Operation 1: Linguistic code competence. Syntax, idioms, patterns, API knowledge, style conventions. How does a proper requestAnimationFrame loop look? What’s the modern way to do matrix rotation in JavaScript? This is what code corpora teach directly, and what fine-tuning reinforces.

Operation 2: Semantic world modeling. Understanding what a Tetris game is. That blocks fall under gravity. That collision means a piece cannot occupy the same space as the floor, walls, or other pieces. That the spawn zone is above the visible board, so y-coordinates can be negative during the first frames of a piece’s life. That Tetris has 10 columns, not 12. That the Nintendo scoring system uses specific values for a reason. That difficulty curves must respect human reaction time.

None of this is code knowledge. It’s world knowledge - spatial reasoning, game design intuition, understanding of physical metaphors and state invariants. It comes from the broad pretraining distribution: Wikipedia articles, game design documents, forum discussions, physics texts.

Fine-tuning on code corpora massively strengthens Operation 1 while eroding Operation 2. The model becomes fluent in the language of programming while losing its grasp on the meaning of programs.

Code fine-tuning optimizes for the form of code, not the function of programs. The coding model is like a translator who writes flawless French but no longer understands what the German source text says.

The Science Behind the Myth

This isn’t speculation. The mechanism has a name in machine learning: catastrophic forgetting - and it’s empirically well-documented.

A 2023 study by Luo et al. demonstrated that catastrophic forgetting is consistently observed in LLMs during continual fine-tuning, and - counterintuitively - that the severity increases with model scale. Larger models have more to lose, and they lose it more dramatically.

Now, the naive objection is: catastrophic forgetting explains cross-domain loss (fine-tune on medicine, lose math). But here we’re fine-tuning on code and asking for code - shouldn’t the domain match?

It doesn’t, because the domain match is an illusion. “Writing a working Tetris game” isn’t a code task. It’s a world-modeling task expressed as code. The actual domain the model needs - spatial reasoning, game physics, design knowledge - lives in the general pretraining distribution, not in the code fine-tuning data. Code corpora teach you what requestAnimationFrame does. They don’t teach you that Tetris has 10 columns.

A Harvard Digital Data Design Institute analysis found exactly this pattern: fine-tuning LLMs on specialized datasets frequently degrades their chain-of-thought reasoning performance, even on tasks adjacent to the specialization domain.

The most illuminating finding comes from an ICLR paper on implicit inference in language models. The researchers showed that fine-tuning doesn’t erase capabilities - it redirects the model’s implicit task inference. The model still “knows” how to reason about spatial relationships and game logic, but the fine-tuning distribution has shifted its internal compass so heavily toward code-pattern-completion that it no longer activates those capabilities when it sees a coding prompt. The researchers could recover natural reasoning capabilities lost during code fine-tuning simply by translating prompts into different languages - tricking the model out of its code-specialized inference mode.

A related finding reveals what researchers call format specialization: the model doesn’t just learn the task, it overfits to the format of the training distribution, and this overfitting occurs within the very first steps of fine-tuning. For a coding model, this means it learns what code looks like far faster and more thoroughly than it learns what code does.

This explains the Tetris results perfectly. The coding model’s output looks like a Tetris implementation. It has the right structure, the right function names, the right patterns. It just doesn’t work like one.

The Benchmark Problem

If coding models are systematically worse at producing functional programs, why do they keep topping the leaderboards?

Because the leaderboards measure the wrong thing.

SWE-bench, the industry’s most prominent coding benchmark, evaluates models on generating patches for real GitHub issues. It has become the metric that labs use to claim coding superiority. But as John Yang, one of SWE-bench’s own creators, has observed: models trained primarily on Python scored impressively on the Python-only benchmark, then failed completely on other languages. He calls this “gilded” performance - shiny on the surface, hollow underneath.

The numbers expose the gap. State-of-the-art agents report over 60% resolution rates on SWE-bench Verified. On SWE-bench-Live, which tests against fresh issues from repositories outside the training data, the best score is 19.25%. That’s not a gap - it’s a threefold collapse suggesting much of the measured “coding ability” is pattern matching against familiar repositories.

One commentator described it precisely: benchmark optimization creates perverse incentives that make models worse at real work. Labs tune models for SWE-bench the same way companies once optimized for keyword density in SEO. The benchmark becomes the goal rather than the proxy.

And the vibes-vs-benchmarks disconnect is documented. Researchers have explicitly noted that some models that feel better in real-world use score worse on benchmarks, and vice versa. The evaluation infrastructure and actual developer experience have decoupled.

What’s Actually Happening

When you fine-tune a general model into a coding specialist, three things happen simultaneously:

You strengthen pattern completion for code idioms. The model gets better at producing syntactically correct, stylistically modern, idiomatically clean code. This is what benchmarks measure and what demos showcase.

You weaken world modeling and spatial reasoning. The capabilities that let a model understand what a Tetris grid is, how gravity works in a game context, why a spawn position might have negative coordinates, or why 10 columns and not 12 - these come from the broad pretraining distribution and are degraded by narrow specialization.

You shift implicit task inference. Even when the model retains reasoning capabilities, the fine-tuning biases its internal prompt classification toward “code-completion task” rather than “problem requiring spatial reasoning, game design understanding, and physics intuition, which must then be expressed as code.”

The result is a model that writes beautiful code that doesn’t work. A fluent bullshitter, in programming terms.

The Uncomfortable Implications

“Coding model” is a marketing category, not a capability description. The label implies superiority at everything programming-related. What it actually means: the model produces code that looks like the code in its fine-tuning dataset. Whether it functions correctly depends on capabilities the fine-tuning may have damaged.

Benchmark scores for coding models measure style, not substance. When a coding model tops SWE-bench, it demonstrates pattern-matching against familiar Python repository formats. It doesn’t demonstrate the ability to reason about novel problems and express correct solutions as code.

For many real-world tasks, a strong generalist may outperform a specialist. If your task requires understanding a domain - game physics, financial logic, scientific computation - and translating that understanding into code, the generalist’s broader world model may matter more than the specialist’s superior syntax.

The fine-tuning paradigm for coding may be optimizing in the wrong direction. If the goal is models that write functional programs, the training signal should be execution correctness, not stylistic similarity to human-written code. Some recent approaches use reinforcement learning from execution environments - but as our Tetris test shows, they haven’t resolved the fundamental tension.

What a Tetris Game Reveals

There’s something fitting about Tetris as the test case. It’s simple enough that any competent programmer can build it in an afternoon. It doesn’t need exotic algorithms or deep framework knowledge. What it needs is a clear mental model of a small, self-contained world: a grid, falling pieces, collision rules, line clearing, a difficulty curve.

It’s exactly the kind of task where world understanding dominates over code syntax - and therefore exactly where coding specialization becomes a liability.

The generalist looked at the prompt and thought: “I need to build a world where blocks fall and collide.” The coding model looked at the same prompt and thought: “I need to produce code that looks like a Tetris implementation.”

One gave us a playable game with rough edges. The other gave us a beautiful corpse.

Next time someone tells you their coding model scores 70% on SWE-bench, ask them to make it build Tetris. You might be surprised by what you find.